The Draft Online Safety Bill was introduced for pre-legislative scrutiny in May 2021, following an extensive, public consultation. It is currently being considered by a Joint Committee of both Houses of Parliament. They are due to report back to the Government by 10 December. The Government will then decide if any changes are needed before the legislation is formally introduced in Parliament.

The Bill is exceedingly complex. When it was published in draft form, three accompanying documents were also released, totaling some 488 pages. MPs and Peers have already raised concerns about the ability of Parliament to effectively scrutinise the proposed Bill, given its size and scope.

Some have welcomed the Bill, saying it will improve the lives of children and young people online. Others though are warning that the Bill is a ‘censor’s charter’ and will have negative consequences for freedom of expression online.

Q: What does the Bill aim to do?

The Bill will put new duty of care obligations on companies to keep users safe but the companies must also have regard to freedom of expression and privacy.

- The Bill aims to protect children and others from a range of online harms. Some (such as images of child abuse) are already illegal. But the plan is to cover material that is considered 'legal, but harmful'.

- According to the Government, this refers to ‘online bullying and abuse, to advocacy of self-harm, to spreading disinformation and misinformation. Whilst this behaviour may fall short of amounting to a criminal offence, it can have corrosive and damaging effects, creating toxic online environments and negatively impacting users’ ability to express themselves online.’

- The Bill will apply to ‘user-to-user services’ and ‘search services’. ‘User-to-user’ refers to an internet service where content is generated by a user of the service and then shared with others. ‘Search services’ refers to search engines not included in the first category.

- A new duty of care will also be put on companies to keep users safe and companies must also have regard to freedom of expression and privacy.

- Since the legislation was introduced, there have also been calls for it to stop anonymity online. These calls intensified in the wake of the brutal murder of David Amess MP.

- To help enforce the legislation, Ofcom will become the new online safety regulator and will be able to issue fines of £18million or 10 per cent of ‘qualifying worldwide revenue’ for non-compliance (depending which is higher).

Q: What are some of the concerns?

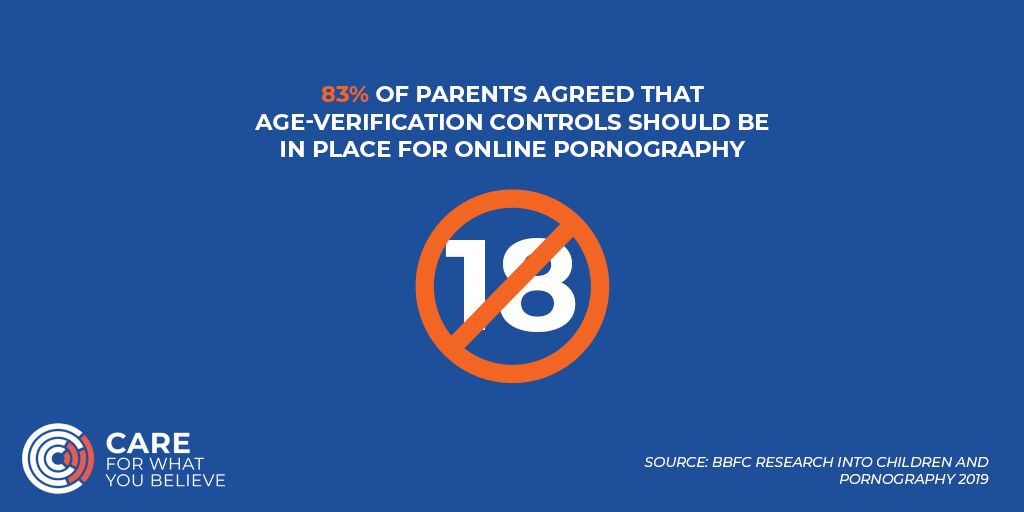

First, there are concerns the legislation does not adequately address children accessing online pornography. The Bill only applies to online services which offer ‘user-to-user’ or search services to the UK. ‘User-to-user’ refers to an internet service where content is generated by a user of the service and then shared with others.

We disagree with the Government’s claim that the most accessed pornographic sites will be covered by the Bill. The current definition of ‘user-generated’ content means porn sites could simply amend how they operate to make sure they are outside of scope.

But what about pornographic websites that offer online porn that is not user-generated? The Bill is silent in respect to commercial pornographic websites that fall outside the scope of the Bill at present. It is also silent on whether the Bill will specifically cover some of the most violent pornography that is concerning because of its impact on violence against women and and girls.

In its final submission to the Online Safety Bill Select Committee, CARE said it ‘disagreed with the Government’s claim that the most accessed pornographic sites will be covered by the Bill. The current definition of ‘user-generated’ content means porn sites could simply amend how they operate to make sure they are outside of scope.’

Secondly, that the Bill is overly broad and could end up restricting freedom of expression online. Definitions will need to be carefully looked at to make sure they are appropriate. Defining ‘legal but harmful’ material is a huge challenge. Some MPs have already raised concerns about the draft legislation, with backbencher David Davis calling it ‘catastrophic for free speech’.

Thirdly, there are concerns that the draft bill gives the Secretary of State (SoS) too much power over the designated media regulator, potentially jeopardising the operational independence of Ofcom. At the moment, Ofcom sets its own standards and the government is not allowed to direct what type of content is regulated. But the draft Online Safety Bill will change that.

Fourthly, some elements of the media have raised concerns that while at the moment content published by publishing companies, like newspapers, is exempt, the Bill sets a precedent which means journalistic content will be next.

Q: What happens next?

Regulating online harms, or even the internet at all is one of the greatest challenges this Parliament will face.

The Committee who are scrutinising the draft Bill will report back to the Government by 10 December. Once the report is published, the Government then decides if further changes are needed. Then, the Bill will then be formally introduced into Parliament and begin the long journey to becoming law.

Given the complexity of what’s being proposed, you can expect this to be a long process. In fact, it would be no surprise if it was 2023 or 2024 before any new legislation was fully implemented.

As a prior example of similar legislation, in 2016, the then Government introduced the Digital Economy Act which also covered regulation of online pornography some of the same areas as the Online Safety Bill and it was three years before that implementation was due to begin.

Regulating online harms, or even the internet at all is one of the greatest challenges this Parliament will face. Social media companies also face a significant challenge. They’re already under huge pressure to take down harmful content as quickly as possible. But wait! If they go too fast and apply the rules too strictly, they’ll get in trouble for taking the wrong kind of content down. Legislators are walking a tightrope between reducing online harm and upholding freedom of expression.

Q: What about pornography?

When it comes to the draft Online Safety Bill, not only is pornography not even mentioned on the face of the Bill, but it is also nowhere near as robust as the Digital Economy Act Part 3 on the requirements for age verification for pornography websites.

As noted above, one of the most alarming aspects of the draft Bill is that as it stands, it fails to deal with pornography. As a contrast, Part 3 of the Digital Economy Act 2017 (DEA) included age verification on all commercial pornographic websites to protect children and a new, independent regulator to crack down on illegal porn. MPs and Peers approved regulations in 2018 to give effect to the new tools to tackle online harm but in October 2019, the Government decided to ditch Part 3 altogether. At the time, Ministers said the new online safety bill would be bigger and better.

Except, when it comes to the draft Online Safety Bill, not only is pornography not even mentioned on the face of the Bill, but it is also nowhere near as robust as the DEA on the requirements for age verification for pornography websites.

Part of the Government’s criticism of the DEA was the fact it didn’t cover social media sites. While this is a fair point, at the moment there is no protection from either social media sites or other pornography websites? CARE is asking the Government to implement part 3 of the DEA and put age checks on all commercial, pornographic websites as soon as possible AND go on to cover social media sites through the new Bill.

We are pleased that the new Secretary of State, Nadine Dorries MP, recently said “I do not believe that the Bill goes far enough in preventing children from accessing commercial pornography” and , “I want to reassure you that we are looking at age verification.”

We hope the Committee will make recommendations that the Draft Online Safety Bill is far more robust on protecting children from pornographic websites and takes action against violent pornography which could lead to violence against women.

Further reading

There's some helpful content out there if you want to understand more about the Online Safety Bill and the changes it proposes to make.

- What to expect from the Online Safety Bill | Guardian

- Everything you need to know about the Online Safety Bill | Indy100

- Twitter says Online Safety Bill needs more clarity | BBC

- Regulating Online Harms | House of Commons Briefing

- Transcripts of evidence to the Joint Committee on the Online Safety Bill | Parliament website

- 5 ways porn harms your child | CARE