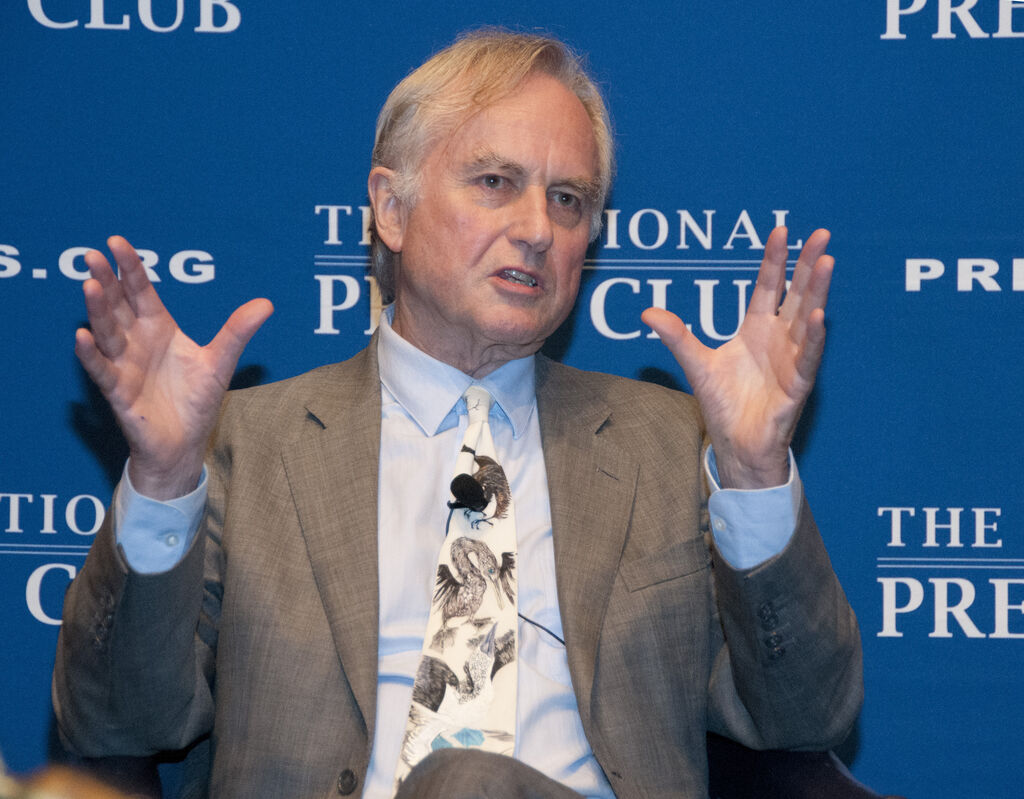

Richard Dawkins, a Christian? The rise of ‘cultural Christianity’ in Britain…

I must confess, I never read ‘The God Delusion’ cover-to-cover. I was only 12 when it was released, and so I rather missed the boat. A few years later I thumbed through a copy in a charity shop, intrigued by what I had missed and interested in hearing what the poster-boy for the New Atheists had to say.

I actually remember being somewhat unimpressed in my quick skim-read, as Professor Dawkins attempted to treat God a bit like any scientific hypothesis (as if God were a part of creation, rather than the Creator), misunderstood various philosophical arguments, and proceeded to say that he didn’t know any historians who took the gospels seriously as historical documents (something I knew to be false, having studied the ancient world at university).

The nadir came when he claimed that a reasonable case could be made that Jesus never existed. Who was his source in the footnotes for such a bold claim? It was a single professor…of French. Ultimately, I didn’t think the book would be worth the £2 I would have had to pay! Being a great biologist does not a philosopher of religion (or a historian) make.

(For the avoidance of doubt, Jesus’ existence is better attested than pretty much any other figure in the ancient world; by way of comparison, the Roman emperor during Jesus’ ministry, Tiberius Caesar, is referred to by 10 sources in the 150 years after his death. Jesus is referred to by 37.)

Richard Dawkins wasn’t alone in his quest to rid the public square of religion and write off people of faith as naive believers in ‘fairytales’. The New Atheists’ arguments were not, in fact, particularly new. But their muscular, vehement approach - indeed, one might call it a pretty insulting approach - towards faith and to the people who hold it, was pretty novel. Just think of the titles of their books: “The end of faith: religion, terror, and the future of reason” (Sam Harris); “God is not great: how religion poisons everything” (Christopher Hitchens)’; and yes, “The God Delusion” (Richard Dawkins).

So it has come as a delightful surprise to many this week to hear Richard Dawkins’ assessment of Christianity - and its place in Britain - almost twenty years on from the high-point of New Atheism’s popularity. In an LBC interview with Rachel Johnson, he declared himself to be a ‘cultural Christian’, declared Christianity to be a ‘fundamentally decent religion’, and lamented the way in which in London, recently, the city was more decorated with symbols for Ramadan than with those of Easter.

At CARE, we are always interested in cultural trends: the narratives and the values our society holds ultimately tend to be reflected in its politics, its government and its legislation.

It’s important not to get too excited at this point, and we’ll dig deeper into the problems with Dawkins' approach later. As Christians, there is sometimes a temptation to latch onto good-news stories and to get carried away (does anyone else remember the rumour about Boris Johnson’s doctor in hospital being a Christian during the pandemic, which suddenly seemed to take over the internet, despite there being no factual basis for it?). To clarify: Richard Dawkins is not actually a Christian. But his words do provide evidence of a shift in the way Christian faith is being talked about within the public square.

In many ways, the New Atheism captured a cultural moment: in the aftermath of 9/11 (and the other terror-related events which followed), in which Islamic faith was used as a weapon by terrorists and suicide bombers, religion was written off by some voices as backwards, regressive, and even dangerous. It was seen as the enemy of the modern world: anti-science, anti-women and anti-progress, trapping its unfortunate adherents in a quagmire of guilt and oppression, all based on (the enlightened voices told us) the myths and fairy-stories of a backwards culture. This was the era of Dan Brown and 'The Da Vinci Code' and of bus adverts saying ‘There’s probably no God, so stop worrying and enjoy your life.’

But the belligerence of the New Atheists has given way to a new feeling: a fear of what might come next. For what the New Atheists did not publicly recognise at the time was that not all faiths are the same.

It is this which is the crucial context for Richard Dawkins’ recent comments. In the interview, he described Christianity as a ‘bulwark’ against Islam. He said that he would not want to replace Christianity with another religion in the UK (‘that would be a disaster’). When it comes to Christianity or Islam, he said, ‘I’m on team Christian’, lamenting Islamic teachings on women and those who are attracted to the same sex. Mindful of not wanting to open himself up to criticism, he made a distinction between Islam and many Muslim individuals, but his point was clear: Christianity was the ‘decent’ religion. Others were not.

His words feel very topical in our current cultural moment: Suella Braverman, the former Home Secretary, came under much criticism last year for saying that ‘multiculturalism has failed’. And yet, at a time when slogans like ‘From the River to the Sea’ are projected onto Big Ben, and we witness march after march, it is difficult to disagree with her.

Yet it is not merely Islam - or indeed, any other traditional religion - which some are concerned about. The New Atheists had seemed to some to hold out the promise of a new dawn, of an era of reason and rationality. And yet, in the aftermath, what has arisen is something they did not foresee: the rise of feelings over facts.

Just consider, for instance, the transgender debate. This is a world in which - for trans activists - science is relegated to a footnote or an irrelevance. Biological sex is trumped by one’s inner sense of self, whether one feels like a man or a woman. Inconvenient problems - such as safeguarding, sports or single-sex spaces - are brushed aside. If anyone dares to question the prevailing narrative, they should be excommunicated (or in modern parlance, cancelled). This is something Professor Dawkins - inevitably, a believer in biology over feelings - has discovered.

The American novelist David Foster Wallace put it like this: “Everyone worships. The only choice is what we worship.” Everyone ultimately looks to something as god, whether it be Jesus or Allah, or in secular circles today, themself.

Or as the adage attributed to GK Chesterton goes: “Once people stop believing in God, the problem is not that they will believe in nothing; rather, the problem is that they will believe anything.”

The New Atheists had sought to direct people away from following the rules of any god, holy book or church, believing that their values were self-evident to everyone: values of tolerance, individual liberty, and reason.

Instead, we live today in a world not too dissimilar to that described at the end of the book of Judges: “in those days Israel had no King; each man did as he saw fit” (Judges 21:25).

The values which the Western world holds did not simply emerge out of nowhere; in recent years, there has been an increasing acceptance that they are part of our Christian heritage. This was first argued by Tom Holland, in his excellent book ‘Dominion’:

“People in the West, even those who may imagine that they have emancipated themselves from Christian belief, in fact, are shot through with Christian assumptions about almost everything...All of us in the West are a goldfish, and the water that we swim in is Christianity, by which I don’t necessarily mean the confessional form of the faith, but, rather, considered as an entire civilisation.”

His argument has since been taken up by Christian thinkers like Glen Scrivener, in his book ‘The Air we Breathe’, and Justin Brierley, who wrote a book entitled ‘The surprising rebirth of belief in God: why the New Atheism grew old and secular thinkers are considering Christianity again.’

Within wider culture, meanwhile, movements like the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship (ARC), led by Baroness Philippa Stroud and Jordan Peterson, argue for a return to our Judaeo-Christian heritage, and a recognition that all humans are made ‘in the image of God’.

For ultimately, Judaeo-Christian values are not inherently obvious to other cultures around the world. When Richard Dawkins laments Islamic teaching around women, he is right to do so. But equally, had he looked back to the worlds of Ancient Greece or Rome, he would hardly have found a better picture there.

Holland explains:

“The dynamic in the Roman world was not between, as it is now, men and women. It was between those who have power, namely Roman free male citizens, and those who were subordinate to them. And essentially the Roman sexual universe was by our lights very brutal. It was a very Harvey Weinstein sexual arena…Now, Christianity radically, radically changes that…And it’s something that offers to women a dignity that no previous sexual dispensation had offered.”

Indeed, it is not just the ancient worldviews with which Christianity came into conflict: it is entirely in contrast to the Darwinian worldview too, the world of the ‘survival of the fittest’, in which the strong can oppress the weak (one manifestation of which, ultimately, was the early 20th century arguments around eugenics which eventually resulted in the Holocaust).

For the radical transformation in attitudes towards women Christianity offered, you can find further transformations with regards to the values of kindness, care for the vulnerable, tolerance, equality, and so much more…

It is no surprise that Judaeo-Christian values have so shaped the world. Indeed, God’s original covenant with Abraham stressed that through him, he would bless the nations: “all peoples on earth will be blessed through you” (Genesis 12:3).

God has always called his people to live lives which are radically different, to be “salt and light”, and to “let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven” (Matthew 5:16).

God is for human flourishing; and it is a wonderful thing that our world has been so impacted by Christian teachings that are for the benefit of all.

But ultimately the true way to flourish as a human being is to encounter God himself. Jesus said, “I have come so that they might have life, and life in all its fullness” (John 10:10). It is only through relationship with him that we can truly live.

And this, sadly, is not something which Richard Dawkins is currently interested in, as he was at pains to stress within his interview. Rather than worrying about any decline in belief in God, he said he was concerned about the destruction of cathedrals and parish churches. When answering on the actual beliefs of Christianity, he reiterated: ‘The things which Christians believe are actually nonsense.’ He seems to be a traditional ‘Christmas and Easter’ churchgoer, who enjoys singing hymns and Christmas carols, and sighs in despair at the message from the pulpit.

But even if Richard Dawkins himself would steer away from belief in God (and although we know that the His Holy Spirit can work miracles in anyone’s life, I suspect Dawkins is so set against anything which conflicts with science as an ultimate authority that he is unlikely to change any time soon) we do live in a cultural moment where people are asking the big questions again: questions about the value of humanity, about what is right and wrong, and whether all cultures really are the same.

The New Atheism has been examined and, having sought to detach Christian values from Christ, on the assumption that they are universally obvious, it has been found wanting; or in the words of Hans Christian Anderson: “The emperor has no clothes.”

Indeed, last year another prominent New Atheist, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, made headlines of her own, declaring that she had not simply become a cultural Christian, but a believing one.

I have also turned to Christianity because I ultimately found life without any spiritual solace unendurable — indeed very nearly self-destructive. Atheism failed to answer a simple question: what is the meaning and purpose of life?

Christian values cannot simply be detached from Christ: indeed, moral values cannot exist in a vacuum full stop: they have to be grounded in something, or someone. It was this realisation which first led CS Lewis to faith in a god (which he did before he came to faith in Christ a couple of years later): he realised that goodness could not just exist as a brute fact, for there had to be something which made it good. He writes in 'Mere Christianity':

“My argument against God was that the universe seemed so cruel and unjust. Just how had I got this idea of just and unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing this universe with when I called it unjust?…Thus in the very act of trying to prove that God did not exist—in other words, that the whole of reality was senseless—I found I was forced to assume that one part of reality—namely my idea of justice—was full of sense.”

But ultimately, we don’t just need a set of values to live by. We need the person who embodied them. In that sense - although I understand what he means by it - Richard Dawkins’ term of ‘cultural Christian’ is really a misnomer. One’s allegiance is either with Christ or it is against him. Paul writes in Romans 10: “ If you declare with your mouth, “Jesus is Lord,” and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Romans 10:9).

It is only through an encounter with Jesus that anyone is truly changed: He is the one who can make the blind man see and the lame man walk; He is the one who touches and restores those on the margins and who challenges our pride and our hypocrisy. He is the one who is gentle and tender, yet overturns tables and stills the storms. He is the one who claims ownership of your life and mine, yet would lay down his own life to save us. He is strong; He is kind; He is challenging, He is radical, you might even say He is dangerous.

But He is good.

Richard Dawkins might find singing hymns and Christmas carols all very pleasant.

But the truth about Jesus is so much more exciting. Let’s take it out again to a world which has forgotten that.